“Impressionism, from Monet to America: Light Crossing the Sea”, curated by The Hyundai Seoul and running from February through the end of May, offers a compelling exploration of how art and music evolved and interacted within the broader flow of historical change. Simultaneously, the global success of renowned Korean pianists such as Cho Seong-jin and Lim Yun-chan is reviving interest in classical music. Art and music are not merely subjects of appreciation; they are vital cultural expressions that embody the spirit of the times and reflect social transformations. This article examines the evolution of Western art through the Classical, Romantic, and Impressionist eras. It also analyzes how representative musicians and painters of each period captured the defining characteristics of their time.

1. Classical Era: mid 18th to early 19th century

The Classical Era, shaped by the Enlightenment, emphasized reason, order, and harmony. It marked the beginning of major transformations, such as the French Revolution (1789) and the Industrial Revolution. Classical music prioritized formal clarity and balance, exemplified by the development of the sonata form, which consists of is structured in three key sections: exposition, development, and recapitulation. Prominent composers of this era include Franz Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and the early-period Ludwig van Beethoven.

The visual art mirrored the music’s emphasis on structure and balance. It upheld the Renaissance values such as humanism, harmony, and rationality. Jacques-Louis David is considered a representative painter of this era.

Haydn: Known as the “Father of the Symphony,” he composed over 100 symphonies. Symphony No. 101, “The Clock,” demonstrates both his wit and structural sophistication. Music critic Charles Rosen noted, “Haydn’s symphonies go beyond mere balance, blending narrative depth and humor.”

Mozart: Works such as Symphony No. 40 and Piano Sonata K. 545 highlight both elegance and emotional depth. Musicologist Alfred Einstein remarked: “Mozart’s music achieves perfect harmony even in the simplest of melodies.”

Jacques-Louis David: In The Coronation of Napoleon, David conveys political symbolism through grand composition and meticulous detail. Art historian Kenneth Clark observed that “David was not merely a painter of history but a visual architect of the era’s ideology.”

2. Romantic Era: Early to late 19th century

Following the Industrial Revolution, the Romantic Era saw profound social transformations, fostering a growing emphasis on human emotion and individuality. With the rise of democratic ideals, the freedom of personal expression to express personal feelings became a hallmark of the arts. Literature and the visual arts flourished, embracing imagination and subjectivity.

Romantic music emphasized emotional intensity, greater structural flexibility, and national identity. Prominent composers of the period include the late Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Frédéric Chopin, and Johannes Brahms. Likewise, Romantic painting centered on emotional narratives and dramatic compositions.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 9, “Choral,” is a revolutionary work celebrating freedom and universal brotherhood. Upon its premiere in 1824, it was hailed as a bold artistic statement.

Chopin: Fantasy-Impromptu demonstrates poetic sensitivity and virtuosic flair. Pianist Alfred Cortot remarked, “Chopin’s works explore the inner depths of the human soul through the piano.”

Delacroix: Liberty Leading the People (1830), a symbol of the July Revolution in France, features a dynamic composition and vivid colors, conveying collective resistance.

Francisco Goya: The Third of May 1808 portrays the brutality of war with raw emotional force, capturing the extremes of human suffering.

3. Impressionism: late 19th to early 20th century

Emerging in late 19th-century France, Impressionism developed in response to rapid industrialization and urbanization. Artists sought to capture fleeting visual experiences and shifting light, focusing on impressions rather than detailed realism. The advent of photography further influenced the movement, prompting a shift toward momentary impressions rather than exact representation.

Impressionist music broke from traditional harmonies and structures, favoring ambiguous atmospheres and vivid tonal colors.

Composers such as Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel rejected conventional tonality and embraced lyrical melodies and innovative orchestration.

Impressionist painters moved away from realism, instead depicting transient effects of light and color.

Debussy: Prioritizing color and mood over formal structure, Clair de Lune blends gentle arpeggios and mysterious harmonies. Pierre Boulez described it as a “painting in music.”

Ravel: In Jeux d’eau, Ravel sonically captures the motion of water reflecting sunlight, abandoning strict counterpoint in favor of organic fluidity.

Claude Monet: Impression, Soleil Levant used color and brushstroke to depict transient light. Though initially criticized, it later came to define the Impressionist aesthetic.

Auguste Renoir: Luncheon of the Boating Party captures a vibrant moment under natural light. Art historian John Rewald noted, “Renoir merged figures and background into a harmonious mass of color.”

While Impressionism focused on fleeting light and color, Post-Impressionist artists explored subjective emotion and individual style. In music, these developments led to even more innovative forms.

Ravel’s Boléro employs a repetitive rhythmic motif, gradually expanding the orchestral sound — redirecting Impressionism toward new sonic possibilities.

Vincent van Gogh: The Starry Night conveys emotional turbulence through swirling brushstrokes and vivid colors. Art critic Robert Hughes described it as “a landscape of the mind beyond what the eye sees.”

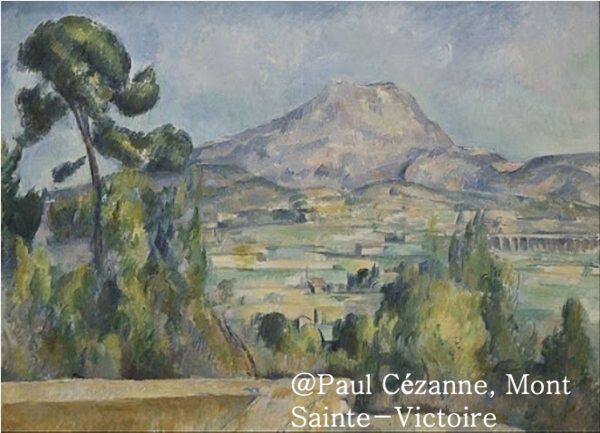

Paul Cézanne: Rejecting traditional perspective, Cézanne stated: “All forms in nature are based on the sphere, the cone, and the cylinder.” His Mont Sainte-Victoire series reflects structural exploration beyond mere surface impression.

Post-Impressionism was not just a stylistic shift but a redefinition of how reality could be perceived and expressed. Music and visual art, though differing in medium, share a common mission: to reflect changing perceptions of the world.

Western arts have evolved in response to societal changes, shifting from the formal structures of Classicism to the emotional depth of Romanticism, and then to the ephemeral beauty of Impressionism. Each era redefined the artistic language, either in opposition to or as an expansion of its predecessor. Today, amidst postmodernism and the digital revolution, we continue to explore new forms of artistic expression. Understanding the historical currents that shaped past arts enables us to better grasp the trajectory of contemporary creativity and consider where the future of art might lead.